PLACES THAT ARE GONE #1: Detroit's "Cadillac"/Conner Stamping Plant

History and tales of exploratory days within the vast expanse of industrial joy that was "Caddy."

If you follow me on Instagram, Facebook or Bluesky, you may know that I have a soft spot for abandoned industrial buildings, and always enjoy going back to many of my favorite shuttered factories and crumbling manufacturing plants across the Rust Belt to reshoot, or in some cases where the facility has been erased through demolition, re-edit old photos taken in past years. One such factory that is no longer with us is a classic abandoned structure in Detroit, Michigan that many an explorer came to know as a photographical gem, and a place where many memories were made in every season. The place I’d like to highlight today is the now demolished Conner Stamping Plant, known by many other names, most comfortably as the “Cadillac Stamping Plant,” or simply, “Caddy.” She was a true lady of the collapsing industrial wastelands of the Rust Belt, as you’ll hopefully soon see. And seeing is believing.

A wintery view of the Conner Stamping Plant (2019)

But first, as always, let me lay in a little history. In the 1880's, Detroit was the center of the industrial revolution, attracting businesses of all kinds from around the world. One of these was the Clayton & Lambert Manufacturing Company, formed in 1891 by two businessmen who made firepots, torches, and other heat tools. As the Dawn of the Automobile literally began rolling, the company expanded into the car market in the 1910's, stamping fenders, hoods, gas tanks and radiators for the dozens of car companies that had settled in the Detroit area. Automotive stamping became such a large part of the business that by 1919 it was spun off into a separate division. A new factory at 9501 Conner Street was built for the Knodell Division, which specialized in stamping and metal work.

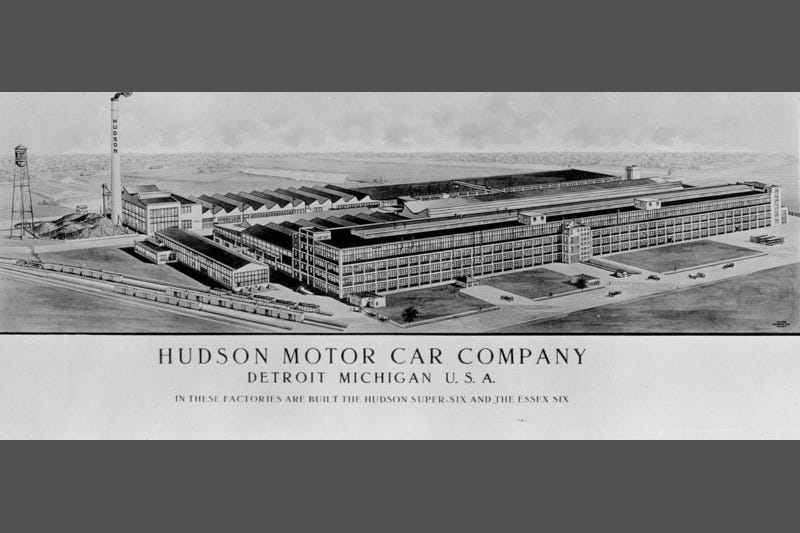

In 1925, Clayton & Lambert sold the Knodell Division and the Conner stamping plant to the then-booming Hudson Motor Car Company. Hudson began expanding the plant, enlisting wunderkind Detroit architect Albert Khan to design multistory additions to the existing buildings. The Conner plant would supply new Hudson factories located to the south, part of a corridor of auto production that would revolutionize the industry.

(photo taken from Detroiturbex.com)

The plant would soon bounce from owner to owner as things in the automobile industry shifted and shunted rapidly. By 1954, Hudson had merged with Nash-Kelvinator to form American Motors. Production of Hudson cars and parts was moved to other factories in Wisconsin, leading to the closure of the Conner plant. In 1956, Cadillac bought the former Hudson plant to make body panels for its cars. A large building to the south was added between 1961 and 1967. Between 1967 and 1973 the space between buildings was fitted with a roof and converted into a warehouse.

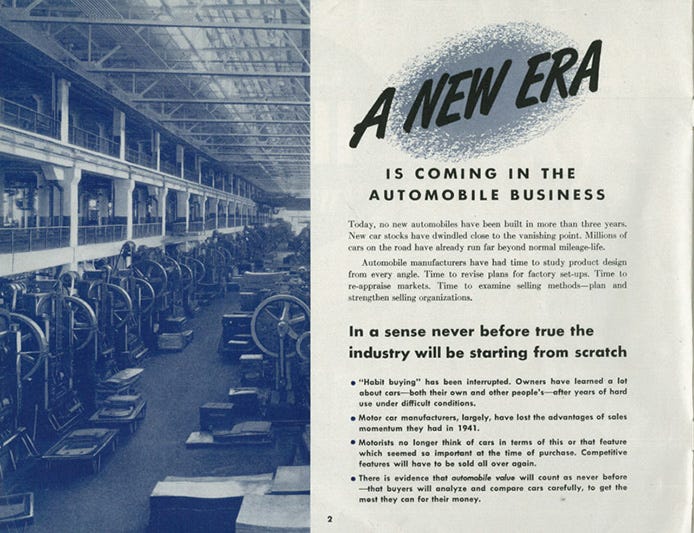

An old ad for the plant, showing the work floor (from Detroiturbex.com)

In later years, in the 1980’s, the plant was known as the BOC Conner Stamping plant, making parts for Buick, Oldsmobile, and Cadillac cars, though the multistory plant was becoming dated and was less efficient than more modern single-story factories. In 1986 General Motors announced that it would be closing the Conner plant in one year, along with 10 other factories. 700 employees at the Conner plant were laid off.

The “Cadillac” years; (from Detroiturbex.com)

For several years the plant was vacant until it was bought by the Ivan Doverspike company in 1993. Ivan Doverspike was a machine tool shop that was founded in 1960, specializing in remanufacturing tools. After a stint in the former Murray Factory, which was later converted into the Russell Industrial Complex, the company moved into the former BOC plant where it would remain for over 20 years.

The Doverspike plant spread out through much of the factory complex, with most of the work being done in the cavernous main stamping hall. Dozens of large tool and die machines were brought in, disassembled, rebuilt, or scrapped on the dirt floor. The adjacent floors were used for storage of spare and new parts. Other parts of the plant were used for storage of boats, vintage cars, and…a massive collection of hockey and baseball cards (that in itself is a strange story, which I’ll touch on later!).

Sometime in the mid 2000's Ivan Doverspike became involved with the Ecorse Machine Company, which had a modern facility in Wyandotte, MI. The Conner plant was eventually used primarily for storage as work was shifted to the Wyandotte plant. In 2013, businessman Bill Hults bought the Conner plant from Ivan Doverspike, announcing that he planned on investing $35-40 million dollars to renovate it into a factory for pre-cast modular houses. Doverspike continued to lease parts of the factory from Hults, moving into smaller and smaller spaces.

Though Hults publicly claimed he was planning on refurbishing and reopening the plant within six months, that turned out to be a complete load of bull-hockey; workers instead were assigned with stripping the buildings of all valuable metals, including copper wiring and the large overhead gantry cranes in the main stamping plant. By 2015, most of the plant was abandoned, though Ecorse Machine continued to use one of the warehouses.

As I alluded to above, the strangest thing remaining was that large collection of baseball and hockey cards left behind after the plant closed. These became the subject of heated controversy after a UK tabloid ran a story claiming the cards were worth over $1 million dollars. The owner of the plant, so the story goes, believed that they would appreciate in value over time, and so had pallets and pallets of them stored on the second floor. Then the guy went and died, leaving them there, abandoned with the rest of the tired and creaking structure. As it turns out, the cards weren’t worth squat. Never were and would never be. And so they became a feature of Caddy’s abandonment, and an endless amusement and curiosity for explorers and photographers that would come over the next years.

Hockey cards galore…

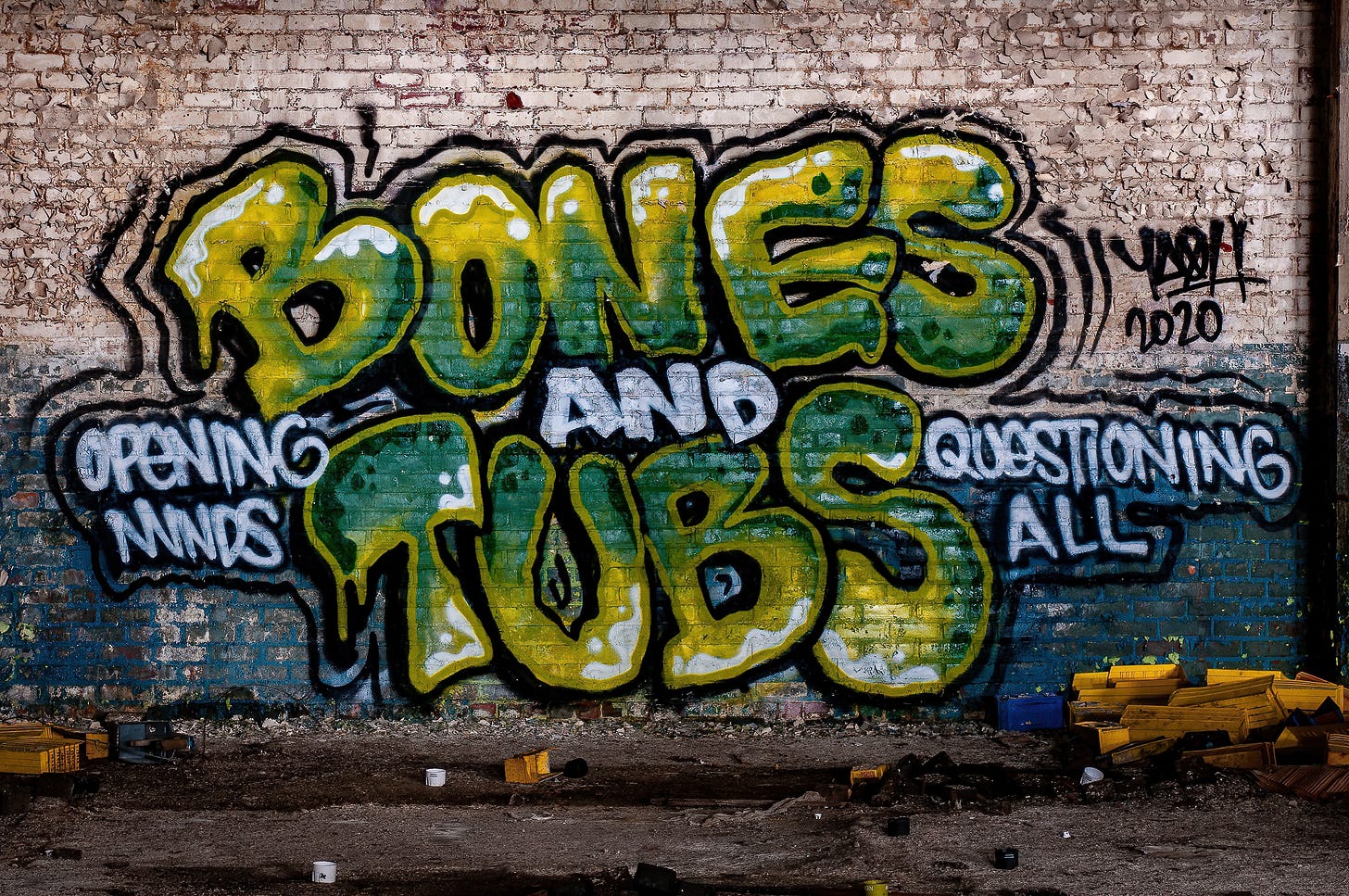

After 2015, the forces of entropy began to inevitably work their way into the cracks, crevasses, long, dim rooms and incredible stretches of the old plant. As happened with so many industrial abandonments in Detroit, armies of scrappers swarmed throughout the building, ripping out and taking whatever precious and semi-precious metals that were left, including structural beams that held up parts of the massive superstructure (something that never ends well). Nefarious local parties started dumping trash, busted up furniture and a whole manifest of unsavory junk onto the plants main floors. As years went by, any possible viability the place would have had as a spot for a new business to move in dropped precipitously. It was now just considered an eyesore and an embarrassment to many people in the Detroit area. Well, for almost everybody. See, the urban exploration community adopted it as it’s own and it became a rather special place for many of us, including myself.

I know that it sounds very strange to those outside of the urban exploration and photography community, but many of the buildings that we frequent gain a sort of “extended family” status among the people who frequent them. We get attached to these locations and consider them a place to go to unwind, practice our photographic art, shoot the bull with a few cold beverages, or otherwise just goof around for some laughs when other avenues of exploration just weren’t working out for that specific day. Cleveland has a similar haunt in the form of the old Westinghouse plant, and Caddy became a very special place to myself, as well as countless Detroit explorers over the last decade. Winter, summer and the spaces in between, we visited Caddy and walked her tire-strewn and cavernous reaches, marveled at the many abstract and colorful urban art pieces that lined her walls and candied up her rooftop, strode across her creosote wood-block flooring and sifted through the ocean of old hockey trading cards that had been left there to rot by the plant’s former and final owner when he passed away. We drank cold beverages on the roof in the summers, cracking wiseass jokes and tossing shards of glass down onto the main floor three stories below from the broken out skylights that lined the high walls of the football field long building.

Caddy was a place so large that you could actually pull your car into the place and park inside while you explored the building, where it was unseen to the outside world and where you could keep an eye on it from any vantage point in the factory. It was a place where you might run into any number of Detroit’s more colorful characters at any time, from gruff and sketchy scrappers to chill graffiti artists; from addled crackheads to aspirant musicians making rap videos; from homeless drifters to drone racers, from boorish kids looking to break things to other explorers and photographers (from Detroit or as far away as California!) who were there for the same reasons you were. Was it trashed and blown out beyond all rescue? Yes. Was it a dumping ground for a sea of used and abused tires that someone eventually set on fire? Definitely. Was it an eyesore for the city, hated by the demolition-happy mayor? Absolutely. But we all saw past those things and saw it as a magnificent piece of history; a monument to things that were, a gargantuan reminder of what could be built when humans put their mind to greatness and a ruined treasure that always yielded new surprises for your camera lens each time you came to wander her vast halls and echoing stairwells, no matter how many times you’d been there before. It was so many things to so many people, and when the word came down last year that it had been purchased with the intent to demolish her, so many people felt a substantial inner loss. Again, I know it sounds bizarre, but that’s what it was like. When the time finally came, we dutifully documented her final days as she disappeared a piece at a time, like we were holding a death watch at the hospital, waiting for the final moment to come. And it sadly, and with utter finality, it did. Now, there is nothing on site which would ever tell you that a massive concrete and metal structure with some serious character once stood there, and in her place, a massive, soulless Amazon-esque warehouse structure was erected; a pathetic substitute for the old lady who once intrigued us all so much and for so long. Now, all we have are the photos and videos we took there when we had the chance to get to know every dark corner, nook and cranny of her dim expanses.

The photos I am putting forth here were taken on a warm early June day in 2020, and little did I know at that time that this would be the last time I would get to experience Caddy as she was. I wasn’t very experienced in the arts of photography at the time, and I was only shooting on my first “big boy” camera, my old Nikon D300, so the shots are NOT what I would expect of myself here and now as I write this. But it was where I was at in those last days. It’s all I have, so it’s all I can offer! If you yourself ever ventured into Caddy, or even better, if you worked there at some point in the past, I encourage you all who have memories of the place to share in the comments and let us all know what experiences you had there as well. With that, I hand off a hearty “Rest in Peace” to a magnificent old building, now consigned to the landfills, but much better, to our memories.

All photos taken by Mr. P. Explores, unless otherwise documented.

Members of my family worked there. I remember hearing the stories as a kid.

These are awesome! And I love that you dig deep into the history of the buildings. I also do my best to document the history of the buildings that I explore. I only explored Detroit once back in 2014, and never did Caddy. I'm not sure why. But these are awesome!